First descent of the Green Monarch Mountains

Story and photos by Ben Olson

|

|

The 21st century is a tough time to be alive for adventurers, explorers, nomads, crazies and edge-seekers. Everything seems to have already been done; every island charted, all mountain ranges climbed by the blind and geriatric, rivers plotted and depths sounded. To do something that nobody has ever done before has become quite difficult.

That is why the first descent of the Green Monarch Mountains by Sandpoint’s Lawson Tate is so noteworthy. To my knowledge, no one has ever skied down those sheer cliffs at the east end of Lake Pend Oreille. To set eyes upon the barren rocks and sheer cliff faces, it seems an impossibility for anyone to ski down such terrain and live to tell the tale.

But one man did this unprecedented feat during the winter of 2008.

Skiing down the Monarchs is insane. Please don’t attempt anything like this unless you are ready to die and/or have the proper experience and resources.

The first descent

The peak of the Green Monarch Mountain, where Tate dropped in Feb. 3, 2008, has an elevation of 5,082 feet. The low-lake level is around 2,048 feet, which provides more than 3,000 feet of vertical drop, at such an angle as to cause severe bowel discomfort.

There are only three avalanche chutes where a descent would be remotely possible, each filled with obstacles, debris, hidden rocks and wrong turns leading to disaster.

It was more than a decade earlier when Tate first toyed with the idea of skiing down that legendary cliff.

“The Fire Storm (in 1991) exposed the rocks on the cliff face,” Tate said. “I was a kid then, living in Ponder Point, and I could see the scars. Once it burned off, there was some talk about a couple of chutes looking like ski runs. Then the question remained: Would there be enough snow, and would you be able to ski the burn areas?”

Since then, the only winter that would have provided enough snow before this monster we have just endured was the fabled winter of 1996-97 – the one old gummers referred to when newcomers complained of all the snowfall last season.

Tate, 27, chatted with some friends about whether it would be possible to ski the chute.

“We decided it would take some recon,” said Tate. “I put my boat in at Hope and buzzed across the lake. Then I sighted three possible avalanche chutes that reached the water.”

With the chutes marked on GPS, Tate hit the next hurdle: logistics. It would take a lot of equipment and a lot of people for this plan to succeed.

The area behind the Monarchs is some of the most inaccessible terrain in the county, with only the High Drive and a handful of logging roads providing access.

“Justin Schuck was my logistics guru,” said Tate. “We’ve been best friends since second grade and he was all aboard.”

Schuck organized two ATVs equipped with snow tracks, one that he drove and the other driven by Todd Sullivan. He also got an uncle, David Schuck, and one of his uncle’s brothers, Dale Lockwood, on snowmobiles. They would shuttle him in.

“We had John Peters from Hope on the Lillian B., a 26-foot welded aluminum fishing boat with a GPS system,” Tate said. “This was our mother ship.”

To round out the crew, Tate roused me from bed, suffering from a wicked hangover, and asked if I would act as photographer and radio operator for the expedition.

The ATV crew would shuttle Tate in, and the Lillian B. was to wait offshore to take him home safely. Everyone met in Hope at 7 a.m. and split ways; Peters and I taking the boat to the foot of the Monarchs and Tate with the other four toward Johnson Creek.

“The plan was to take the High Drive to the closest point as the crow flies to the GPS position I marked,” Tate said. “We rallied up as far as we could and left the main road to a spur road leading off toward Kilroy Bay. We took a few hours to find the right switchback and used topo maps to determine the route to ascend the ridge of the Green Monarch Mountain.”

|

The ideal chute the party marked was just west of a ridge leading northeast away from the highest peak of the cliffs. One wrong turn would lead Tate too far east, possibly stranding him atop an 800-foot, sheer cliff face.

“It was really dense fog most of the way,” Tate said. “We couldn’t tell what direction was what except for the GPS.”

When the snow machines could travel no farther, the crew put on snowshoes and hiked a difficult sidehill toward the ridge.

When they reached the correct ridge, most of the crew had returned to their snow machines. “Schuck and I sidehilled far in where we could get radio contact with the Lillian B. At this point, we had to call in our coordinates to the boat, and they would locate us on their onboard GPS and tell how far we had to go in which direction.”

Schuck and Tate bid farewell atop this ridge, still in the fog layer, without a clear view of the lake yet.

Tate took the GPS, the radio and a topo map to navigate with. He also took off his skins, turned on his avalanche beacon and put on the AvaLung™, a device that assists breathing if buried in snow. After snapping on skis, he was ready to descend.

Tate skied a few hundred vertical feet down the ridge – mostly spaced-out snags and big, wide areas of snow.

“I had little confidence I had the right chute when I decided to go for it,” Tate said. “I couldn’t see the boat and the boat couldn’t see me, so we communicated primarily with GPS coordinates. I felt like they had an idea of where I was, but without a visual sighting, it was pretty hairy.”

Tate was finally able to see the boat, just a dark speck 2,500 feet below on the lake. After patient searching with high-powered binoculars, the crew on Lillian B. obtained visual contact on Tate’s position and verified he was in the right chute.

“When they had visual on me, it was a rush,” Tate said. “Now I just had to follow the chute down.

“When you look up at the Monarchs, it doesn’t look skiable because it has big snags and obstructions everywhere, but in reality, you’re so far away from the top of these mountains, it’s a mirage. From the top, it’s steep and open and smooth. It’s the equivalent of skiing down something like Headwall, but much steeper – consistently steeper than anything on Schweitzer.”

From the boat, when I got visual of Tate, he looked like one of those tiny snowboard dudes on a Kokanee bottle; just a mere speck of arms waving ski poles around in the air.

Tate cruised down the rest of the chute with confidence, stopping occasionally to check the radio and the stability of the snow pack, and also to let his legs rest a bit.

“This was definitely the longest run I’d ever taken in my life,” he said. “After I passed the halfway mark, it got nasty and I had to get more technical. Now you’re in a real avalanche chute with debris. It was intimidating, because the sluff was moving a bit. You get into a whole new dimension when you’re skiing on snow that actually moves beneath you, too.”

Tate successfully descended the avalanche chute down to a wall of snow that hung over into the lake. The Lillian B. stood by to pick him up.

“I was able to ski right into the boat,” Tate said, smiling.

Tate was greeted from the boat with shouts of triumph and a 4-pound mackinaw caught by John Peters.

Mission accomplished

The first descent of the Green Monarch Mountains on skis. A new frontier. A first in this era of seconds and thirds.

The Green Monarchs have been gazed upon by thousands of awestruck eyes over the years, and they sit there, just across the lake. Yet, it had taken until then for anyone to meet the challenge of a first descent on skis.

“I like the idea of a challenge,” Tate said. “With this Monarch ski mission, we needed reliable recon, a support crew and the right equipment. It’s not stepping off the chairlift.”

The mission was organized more like an Arctic expedition than a backcountry ski run.

“We had ATVs, snowmobiles, a sweet boat, GPS, VHF radios and all kinds of timing issues to work out. If it all doesn’t come together, it doesn’t happen,” Tate said. “It was a heavily planned and calculated mission, and that’s why it ended up successful.

“I love the lake, I love the mountains, I love this area. Skiing the Monarchs put it all together for me.”

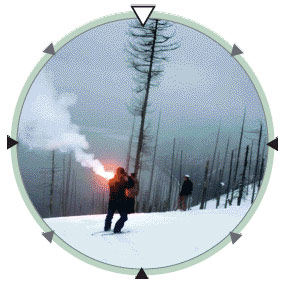

Not to be outdone, two more skiers – Matt Shriber and Cody Lile – descended the same chute the very next day. The mission went a bit smoother the second time around, especially with the addition of flares to give instant, visual recognition from the boat.

This time, however, Tate watched comfortably from the boat.

|