|

|

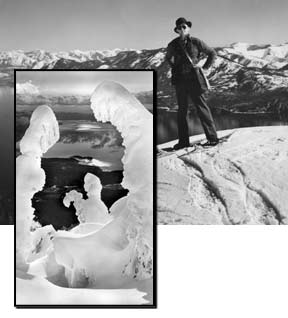

Background photo by Hazel Hall and

Moonlight Tête-à-Tête by Ross Hall

|

Following Ross Hall’s footsteps

Winter adventures in photography

By Kevin Davis

High on a ridge top in the Cabinet Mountains, my skis swish quietly through the cold, powdery snow of January. My path wanders curiously, as if I am in an art museum, but here the only color is white. I can’t help but feel that I have wandered into a Ross Hall photograph, one that pictures a row of beastly forms drooping and swaying in a scene that captures the essence of fantasy. On sojourns like this, I find myself traveling through galleries of “snow ghosts,” following in the footsteps of one of Sandpoint’s own, world-famous photographer Ross Hall, who died in 1990.

The very first time I saw snow ghosts, I became enamored with the whimsical quality of these fantastically transformed trees heavily laden in windswept snow. But it was the photographs of Ross Hall and the stories behind them that completely captivated me.

It was Jan. 5, 1932, and out of the snow-white surroundings a train steamed into the Northern Pacific Railroad depot in Sandpoint. It must have been the warm welcome of many newly found friends that quickly acclimated the native Texan and his new bride, Hazel, to the 3 feet of snow that lay on the ground that cold day. Ross Hall moved to the Great Northwest to pursue a career in photography. In the fashion of pioneers who traveled this land before him, he pursued his occupation with a zeal that revealed many a great discovery. Through the years, his winter exploits became the subject of local legend, and his photography bestowed wonder on a unique and magical landscape known to few.

Ross had many passions, but his love of nature and the outdoors seemed to be a particularly strong compulsion. Naturally, his path merged with energetic mountaineers, such as Matt Schmidt and Dr. Neil Wendle. They became good friends and longtime mountaineering partners. Wendle was a photographer as well and assisted Ross on numerous winter trips. One such excursion in 1939 with Wendle resulted in one of Hall’s most famous photos, “Moonlight Tête-à-Tête.” Hall and he ventured up into the Cabinet Mountains above Hope bright and early, as was customary for their winter outings. Up in the high country Hall discovered something that caught his eye. What he saw was a pair of snow ghosts leaning toward one another, as if having an intimate conversation, a tête-à-tête. To him, the pair represented David Thompson, the geographer and fur trader, and his Native American wife, Charlotte. He took a photograph of the snow ghosts during daylight. Then, he and Wendle waited six hours until dark and the moonlight was just right to capture the reflection off the water around Memaloose Island, a native American burial site – not far from David Thompson’s first trading post in this country, the Kullyspell House. The double exposure created a serene communion between the mountains and the lake and a warm intimacy focused between the two figures. But it must have been a cold hike back down.

He must have enjoyed the cold, or maybe it focused his eye more acutely on his icy, hard-edged subjects. He roamed these mountains more than most people, and, inevitably, while going to extremes, a mountain man runs into some extreme situations. On a winter trip, for instance, to Chimney Rock with several friends, they were subjected to an absurd swing in temperature. In a matter of hours the temperature dropped nearly 70 degrees. They were not prepared for that type of cold, and the three of them had to huddle together in one sleeping bag to make it through the night. If Hall would have taken that picture he may have called it “Sleeping Bag Tête-à-Tête.”

Traveling on snowshoes, wearing his greatcoat, woolen flannel shirt “and often a tie,” says his son Dann Hall, and trailing a sled with his gear, which weighed as much as 70 pounds, was Hall’s modus operandi. Climbing 4,000 vertical feet to get a shot was all in a day’s work. All this belies the fact that he was told by doctors to lead a sedentary lifestyle after a bout with rheumatic fever left him bedridden for two years in his early 20s. During this time Hall gained inspiration by reading the Bible, The Journals of Lewis and Clark and Shakespeare. It was his memory of a passage out of Julius Caesar which read, “I’d rather be a hound baying at the moon than a Roman such as you,” that inspired the photograph entitled “Shakespeare’s Snowhound.”

His proficiency at winter travel and survival was incredible. His technical ability with the camera unwavering, and the two, combined with his determination to accurately portray his surroundings, resulted in national acclaim. “The Forest Christening” was Hall’s first photograph to receive national attention and was published in The New York Times in 1933. His unique vision established him as one of the first photographers to elevate mountain winter scenes to an art form. With that accomplishment, he was a pioneer in the truest sense.

•••

I had a winter experience a few years ago that made me reminisce on some of the experiences Ross Hall must have had while exploring the backcountry in search of photo subjects. It was a perfectly crisp winter day in January, not a cloud in the sky. I was touring at the top of Baldy Mountain overlooking Sandpoint. It had been a bountiful winter for snowfall, and snow ghosts stood randomly all around me as if they were groups of guests at a party, and I was just mingling. I was turning to head down the mountain when a distinctive shape snapped my attention at 180 degrees. I couldn’t believe I was staring at a perfect profile of David Thompson. I don’t know exactly what he looked like, but the icy rendition before me sure was convincing.

Below the sockets of his squinting eyes drooped a long nose like an icicle. His beard fell softly on his chest, and on his head was a cap complete with a tassel. In a suggestively contemplative manner, his gaze was fixed out over the lake. I wondered if this was how Hall’s subjects came upon him – if they jumped out at him or if he ventured far and wide to look for them. I was so excited I unabashedly snapped a whole roll.

That thrill has captivated me ever since. So into the wintry mountains I go with camera in hand. Sometimes my experience is a solitary glide through a magical forest. Every now and then I encounter a unique figure that entices me to take a few shots. Once in a great while I get giddy when I see an utterly fantastical creature, and it leaves me incredulous that something like that could just have randomly occurred by natural forces. As fleeting as these moments are, it convinces me that, to have compiled such an array of extraordinary images, there aren’t many places in these mountains that Ross Hall did not visit. In the winter world of these wondrous northern Idaho mountains, I always feel that I am following in his footsteps.

Collecting, viewing Ross Hall photographs

If you’re looking to collect images by Ross Hall, several galleries carry his work in Sandpoint: Artworks Gallery, Cabin Fever, TimberStand Gallery and Hallans Gallery, home to the Ross Hall Collection. To appreciate his art even more, see the collections at the Bonner County Historical Museum and at The Old Power House on the first and second floors. Other public Ross Hall art displays are found at Eichardt’s and Fritz’s Frypan, where there are historic downtown Sandpoint photos; Safeway, Tomlinson Black Real Estate, Action Agency, Stephen Smith Agency and the Hydra Restaurant; as well as inside the Selkirk Lodge and the Alpine Shop at Schweitzer.

|