|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

.jpg) |

The most dramatic evidence for megafloods is in eastern Washington's Channeled Scabland .Photo by Tim Cady |

The rate of those floods, geologists say, flowed 10 times greater than all the world's rivers combined – up to 1 billion cubic feet per second. Geologists believe the major source of that water, Glacial Lake Missoula, held up to 530 cubic miles of water, or half the volume of Lake Michigan, an immense amount that ultimately would break loose, and run faster and deeper than imaginable. And it did so repeatedly, a hundred times or more during the last Ice Age.

"One billion cubic feet per second is pretty dramatic, and the fact that it spread out for a hundred miles across the Scabland is pretty significant. Most rivers are a mile or less wide," said geologist Bruce Bjornstad, a senior research scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and author of "On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods."

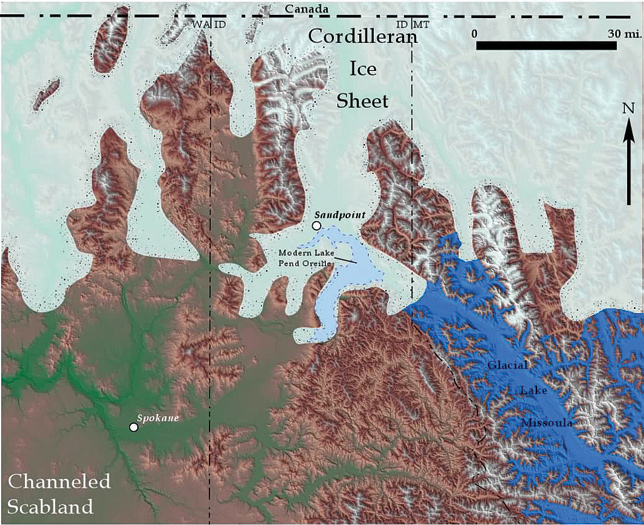

In its wake, the catastrophic Ice Age floods left behind a string of nine lakes in northern Idaho and northeast Washington, punctuated by the question-mark shaped granddaddy of them all – Lake Pend Oreille. It was here that icy fingers from the Cordilleran ice sheet crept south and dammed the Clark Fork River, ultimately forming Glacial Lake Missoula near the Idaho-Montana border.

This great inland sea spread east into Montana for 200 miles. And that ice dam was as large as 23 miles wide, 35 miles long and a half a mile high. Over the years lake water was able to permeate the ice dam until it failed and a humongous flood was unleashed, bursting out the southern tip of modern-day Lake Pend Oreille at Bayview and then over the Rathdrum Prairie, with some water spilling over and heading north and west up the Hoodoo and Blanchard channels to the Priest River Valley. The waters primarily rushed through the Spokane Valley and onto the basalt-covered landscape of eastern Washington, furiously finding their way to the Columbia River and on to the Pacific Ocean at speeds up to 80 mph.

In northern Idaho, where the bedrock was hard granitic and metasedimentary rocks, mostly quartzite and argillite, the Ice Age Floods left behind rounded mountains, glacial lakes and a fertile valley underlain by a vast aquifer.

As the ice-laden waters swept over the Palouse loess and plucked at the basaltic bedrock of Washington and Oregon, they left behind a much different scene: channels, coulees, rock basins and benches, giant bars, mesas and buttes, and other features characteristic of the region south and west of Spokane called the Channeled Scabland.

Northern Idaho's higher elevation and different weather patterns account for its lush, green valleys and forested hillsides, in sharp contrast to the barren, semiarid Columbia Plateau that lies downstream. The vastly different landscapes make it hard to believe that the same Ice Age floods sculpted both regions.

Wherever the megafloods went, they scattered thousands of so-called "erratics," misplaced and oversized boulders that are of a different rock type than the underlying bedrock. Rafted in on icebergs transported by turbulent Ice Age floods, some weigh as much as 100 tons and resemble a battered Volkswagen camper – with the top up.

A scientist and his 'outrageous hypothesis'

Since the Ice Age floods happened before recorded history, it took the keen eye and mind of an unconventional Seattle high school science teacher to realize a hundred years ago that those Channeled Scabland features must have been formed by water. In 1910, at the University of Washington, as J Harlen Bretz pored over the just-released topographic map of eastern Washington's Quincy Basin and its cataract at Potholes Coulee, the seeds were planted for what would become a controversial theory that would rattle the foundation of a fairly new science: geology.

That biology teacher, Bretz, later became a geologist and was expected by his colleagues to conform to the accepted thought of uniformitarianism, the fundamental geologic principle that geologic processes and natural laws now operating to modify Earth's surface have acted in the same regular manner and with the same intensity – slow, gradual and steady – throughout billions of years of geologic time. Those uniformitarians pulled the strings at the U.S. Geological Survey, and they staunchly clung to the belief that past geologic events could be explained by phenomenon and forces observable today.

Still puzzled years later by those topographic maps, Bretz, by now a geology professor at the University of Chicago, ventured to the dry and dusty Channeled Scabland with his students to do fieldwork in the summer of 1922 and published his first scientific paper on the region in 1923. He followed up that initial treatise with 12 more papers outlining all the evidence for what he called a great "Spokane Flood" during ensuing years of more and more fieldwork and refined interpretations. His hypothesis smacked of catastrophism, the opposite of uniformitarianism, and his detractors were many – namely all his peers. They derided Bretz at his presentation in 1927 at the prestigious Cosmos Club in Washington, D.C., ("the closest thing to a social headquarters for Washington's intellectual elite") and continued their contemptuous scorn for decades.

Nevertheless, Bretz trusted his scientific observations and doggedly upheld his "outrageous hypothesis" about the Spokane Flood even though he couldn't pinpoint its source (originally he envisioned a single flood). However, one of his colleagues, Joseph T. Pardee, had written Bretz in 1925 to suggest that the source of his controversial flood may be Glacial Lake Missoula. For reasons unknown, Bretz didn't investigate Pardee's hypothesis himself – didn't even take an excursion to Pardee's home state of Montana nor to northern Idaho – and thereby didn't whole-heartedly accept the connection until years later.

Even if Bretz had visited northern Idaho and Lake Missoula he may not have "seen the light" and been convinced of a connection with the Scabland. Features aren't as obvious until viewed from the air, which generally wasn't done back then.

"As early as 1930 Bretz acknowledged Lake Missoula as a possible flood source and later in 1933 even placed Lake Missoula on a map relative to the Scabland," said Bjornstad. "Bretz wasn't convinced though since he thought the ice sheet extended much farther (to near Spangle south of Cheney) and couldn't imagine how floodwater could penetrate an ice dam 100 miles long. It wasn't until many years later that geologists reinterpreted the edge of the ice only got as far as Bayview."

Perhaps, Bretz was just as human, stubborn and prone to disbelief as his skeptical colleagues. Unwittingly, he made the same mistake they did: failing to visit the area in question.

He did attempt to identify the source for his Spokane Flood though. He traveled to British Columbia and checked out where volcanoes erupted under the ice sheet.

"At the time he believed this was a more likely source than Lake Missoula. However, since he couldn't positively identify where the water came from, he chose to focus on what he could defend – that a huge flood or floods passed through southeastern Washington and the Columbia River Gorge," said Bjornstad.

Some modern-day geologists think that Bretz's hypothesis would have been accepted sooner had he investigated Pardee's evidence and considered his assertion that Glacial Lake Missoula and the Spokane Flood were connected, as brought out by author John Soennichsen in "Bretz's Flood."

Pardee worked for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and spent most of his 32-year career studying geology in the Northwest, with a particular emphasis on Montana. He attended Bretz's ill-accepted lecture at the Cosmos Club but didn't speak up about the possibility that those preposterous floods could have come from Pardee's Glacial Lake Missoula. One could imagine his caution and trepidation among his peers and superiors from the USGS as they turned on Bretz following his presentation. Soennichsen wrote about an unsubstantiated rumor that Pardee whispered to a nearby colleague, "I know where the water came from."

Vindication for Bretz didn't start to come until 1940 when Pardee presented his findings concerning Glacial Lake Missoula – aha! the source of all that water! – to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Seattle. Pardee had discovered a key piece of evidence: giant current ripples clearly visible on aerial photographs. Whereas Bretz was humiliated at his 1927 presentation (he called it an "ambush"), 13 years later Pardee received a standing ovation. Later in 1942 he published his work in the Geological Society of America Bulletin.

"Pardee didn't come out and say there was a flood like Bretz did. He let his audience come to this conclusion on their own," Bjornstad said. "I think Pardee was more diplomatic and less arrogant than Bretz, which made it easier for his peers to believe him."

In 1952 Bretz returned to eastern Washington for his last scabland fieldwork and published a key paper four years later with lots of aerial photographs, including giant current ripples in the Channeled Scabland. It was then that Bretz announced there may have been more than one flood.

"This is about when his fellow geologists started to believe Bretz was right," Bjornstad added. More acceptance and vindication for Bretz came in 1965 when fellow geologists visited the site of the flood-wrought Columbia Plateau. After seeing the landscape for themselves, they wired a telegram to the 82-year-old Bretz: "We are all now catastrophists!"

Bretz helped other geologists think outside the box as they began to consider the evidence for other catastrophes that produce dramatic change during short-lived events, such as tsunamis, volcanic eruptions and meteor impacts. In geologic time, a thousand years or so is just a blink of an eye, and that's all it took for the ice dam at the Idaho-Montana border to form and repeatedly fail, again and again, unleashing recurrent floods that each drained in a few days.

Telling the floods' story

Shaded-relief map of glacial ice dam that impounded Glacial Lake Missoula, which rose to a maximum elevation of 4,250 feet. Illustration by Bruce Bjornstad, "On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods: The Northern Reaches"

Today, northern Idaho's residents and visitors enjoy many features sculpted by Ice Age floods, but few know their source or recognize the remarkable or more subtle flood features for what they are. Each year thousands of people visit Farragut State Park at the southern end of Lake Pend Oreille, but only a fraction comprehend what they see in the steep, glacial-beveled slopes beside the lake or in the erratics and natural ice-melt sinkholes dotting the park. Many stop along Idaho State Highway 200 and admire the precipitous Green Monarch Ridge but don't realize a massive tongue of ice once plowed into it and created an ice dam.

The U.S. Congress, though, passed a bill in 2009 that was signed into law by President Barack Obama to create a first-of-its-kind Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail, which will facilitate expansion of public awareness about the megafloods. The trail will be a network of marked touring routes along the 700-mile-long path of the floods through Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon, with several special interpretive centers at existing public facilities such as visitor centers. This "park without boundaries" will tell the story of the floods, beginning with the work by pioneering geologists Bretz and Pardee, who brought the cataclysms to light.

In northern Idaho, meanwhile, the story of the megafloods has been limited to an interpretive display along Idaho State Highway 200 and the occasional campfire program at Sam Owen Campground or Farragut State Park. But in 2005, a few geologically inclined folks formed a local chapter of the Ice Age Floods Institute to facilitate an exchange of information on the region's natural geologic heritage.

Dubbed Coeur du Deluge, translated meaning "heart of the floods," the chapter has held several field trips, some led by Idaho State Geologist Roy Breckenridge. These flood fans trace the outburst channel from Bayview through the Hoodoo Valley, for example, or visit Hope and Clark Fork to view glacial striations and other evidence for glaciation.

"We've got so much interest and momentum," said chapter President Sylvie White, who owns Maps & More. "Most people who come into the store are amazed that we were under 2,000 feet of ice."

Relic flood features

Author Bruce Bjornstad lists several flood features in what he calls the "ice dam breakout area" in his second volume of "On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods," due to be published this summer by Keokee Books (see story, opposite page). Gene Kiver, emeritus professor at Eastern Washington University is the coauthor.

Those areas affected by the breakout of Missoula floods include Lake Pend Oreille, the Rathdrum Prairie, Spokane Valley, and the Pend Oreille and Little Spokane river valleys.

Following are five of those flood-formed features in the panhandle and their geologic interpretations excerpted from Bjornstad and Kiver's new book.

Purcell Trench Ice Lobe: Ice-sculpted and polished bedrock, beveled slopes, glacial till and erratics. Best observed from Cape Horn Road northeast of Bayview and Idaho State Highway 200 along the north side of Lake Pend Oreille or Green Monarch Divide, Mickinnick, Mineral Point, Cape Horn and Farragut Shoreline trails. During the Ice Age a huge tongue of ice thousands of feet thick flowed south from Canada along the Purcell Trench bounded by the Selkirk Mountains on the west and the Cabinet Mountains to the east. The massive tongue of ice plowed into the Green Monarch Ridge splitting into the Clark Fork and Lake Pend Oreille sublobes, creating the ice dam for Glacial Lake Missoula. The bedrock basin beneath today's Lake Pend Oreille lies 600 feet below sea level as a result of Ice Age erosion; 1,500 feet of glacial sediments separate the lake bottom from the underlying bedrock. At 1,150 feet deep, Lake Pend Oreille is the 13th-deepest lake in the world!

Green Monarch Ridge Buttress: Rocky ridge 3,000 feet tall that deflected the south-flowing Purcell Trench Lobe of glacial ice. Best observed from interpretive display along Idaho State Highway 200 or Green Monarch Ridge and Mineral Point trails. A flow of ice diverged with one tongue that went east up the Clark Fork River Valley and a second tongue that headed south into the Lake Pend Oreille trench. The tall north face of the ridge was oversteepened and beveled by the grinding action of the ice. Thousands of feet of ice pressing hard against Green Monarch Ridge created a temporarily tight seal for Glacial Lake Missoula.

Rathdrum Prairie Outburst Plain: A broad, mostly featureless sediment apron in the area of ice-dam breakout for Glacial Lake Missoula. Best observed from Cape Horn Road northeast of Bayview and Cape Horn Trail. The outburst plain is composed of bouldery flood deposits, hundreds of feet thick. The plain is slightly elevated, lying 300 feet above the south shore of Lake Pend Oreille. The surface of the plain is covered with a network of low-relief braided channels, giant current ripples and oversized ice-rafted erratics. A string of kettle holes lies at the upper end of the outburst plain, left behind from the melting of sediment-covered ice blocks. Today there is no surface drainage across the outburst plain because of the coarse nature of the flood deposits. Rainwater and snowmelt quickly drain into the porous flood sediment, preventing any surface runoff.

Hoodoo Channel: Sinuous channel incised into the Rathdrum Prairie Outburst Plain. Best observed along U.S. Highway 95, three miles north of Athol. The Hoodoo Channel formed from the melting ice from the Lake Pend Oreille sublobe or possibly from much smaller Missoula flood(s) at the end of the Ice Age. The Rathdrum Prairie Outburst Plain proved too high for the Hoodoo Channel, which forced all its drainage northward toward Priest River and into present-day Pend Oreille River Valley.

Spirit Lake Giant Erratics and Current Ripples: Elevated flood bar of the western Rathdrum Prairie Outburst Plain. Best observed from roadcuts along Idaho State Highway 54, a few miles east of Spirit Lake, where coarse gravel and sand compose a series of rolling, giant current ripples. Several giant erratics lie on either side of Idaho State Highway 41, two to three miles south of Spirit Lake. The orientation of the giant current ripples reveals that they were deposited by a flood moving northwest, although other ripples farther south are oriented to the southwest. This suggests that a northern escape route for the Ice Age floods via the Blanchard Channel was temporarily open when this bar was flooded. Giant, angular, ice-rafted erratics locally lie atop the ripples. The giant boulders, composed of granodiorite, are true erratics since they are different than the gneiss bedrock that underlies this area.

Geological field guide explores Ice Age floods' northern reaches

Following up on his 2006 book "On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods," geologist Bruce Bjornstad joined forces with Emeritus Professor Eugene Kiver to guide readers upstream – northward into the Channeled Scabland and northern Idaho – in the second book to be published by Keokee Books in July.

While the Channeled Scabland contains the evidence for megafloods that is most striking and dramatic, northern Idaho has its fair share of flood-shaped features, including magnificent Lake Pend Oreille.

The coauthors cover the northern reaches, beginning at the Idaho-Montana border, where an ice dam formed and created Glacial Lake Missoula. They explore dozens of flood features, many found nowhere else on Earth, and present dozens of trails and tours directing readers to experience, firsthand, the striking aftermath of the cataclysmic Ice Age floods.

The book defines 29 types of landforms, describes 65 flood-formed features, and provides a guide to 39 trails, five drives and two aerial tours.

For more information about "On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods – The Northern Reaches," look up http://www.KeokeeBooks.com.

The entire contents of this site are COPYRIGHT © Keokee Co. Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved.