|

dd |

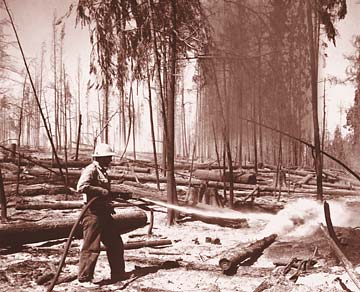

| A firefighter hoses down a smoldering log during the Sundance Fire. |

1967: The Lost Summer

Sundance Fire remembered

By Dennis Nicholls

1967, the summer when all eyes were on northern Idaho, was a time when wildfires burned with a ferocity seldom seen. “It seemed like a long, wet spring, that suddenly dried up,” said Bill Stockman, 74, who worked in the Bonners Ferry Ranger District 35 years ago. The result is well-known today as the Sundance Fire.

Lightning pounded the Selkirk and Cabinet mountains that summer, causing dozens of forest fires. Most were extinguished by a burgeoning firefighting force before they could escape and grow; some weren’t. Thousands of firefighters from across the country converged on North Idaho to battle the fiercest blazes in the nation.

“The fire season in northern Idaho developed quite normally (in 1967), and in the first three months showed characteristics of an average fire season,” wrote Hal E. Anderson in a report for the Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

The first critical date was Aug. 11 when, Anderson observed, the fire danger index reached its highest level in 13 years. A thunderstorm left five smoldering fires on Sundance Mountain.

The fifth fire was spotted Aug. 23 near the lookout, but it was quickly surrounded by fire lines and crews, who worked on the blaze for the next five days. While other fires in the Panhandle raced out of control, Sundance seemed to be well in hand on Aug. 29.

A little after 10 o’clock that night, however, word came into headquarters at Coolin that fire activity had increased, and Sundance had jumped its containment lines. Over the next eight hours, it grew to more than 2,000 acres. From the town of Dover, the initial blowup of the Sundance Fire was “an awesome sight,” remarked Bud Moon, 78, who lived there at the time. “Smoke was coming up over Schweitzer and you could see the glow in the dark sky, a dull red glow.”

That night’s fire activity, however, proved only to be a spark compared to what came on the wind two days later.

Vern Eskridge, 67, was transportation dispatcher for many of the fires and was up Pack River the day before Sundance first jumped its perimeter. At 3 a.m. on the 30th he got word that it was making a run. Strengthening winds pushed embers into Lost Creek that afternoon; residents in Naples reported ash falling from the skies.

|

|

Vern Eskridge and Bill Stockman, right, who helped quench the infamous fire 35 years ago.

|

Though Sundance doubled in size by early morning on the first of September, the flames were still confined to Sundance Mountain south of Soldier Creek at noon; then in blew a strong southwest wind and two hours later one of the most spectacular fire runs ever witnessed began its deadly tear to the northeast.

On the back of fire-induced winds gusting to 95 mph, Sundance Fire raced 16 miles in nine hours. Once it crested the Selkirk Divide, it burned across the entire Pack River drainage and over Apache Ridge – more than 10 miles – in three hours. It was during the height of this firestorm that Luther P. Rodarte of Santa Maria, Calif., and Lee Collins of Thompson Falls, Mont., were killed while hiding beneath a bulldozer.

Stationed at the lookout tower on Roman Nose, Randy Langston, 18, was forced to seek cover from the rapidly advancing wall of flames. He was quoted in National Geographic a year later: “(A) rock shelf had an overhang, and I wedged back under it as far as I could. Flames began roaring over it. I saw blazing branches as long as my arm fly past the overhang and down into the forest around the Roman Nose lakes.”

Langston was rescued by helicopter the next day amidst the smoldering ruins of a vast, blackened landscape, while Moon, then county coroner, traveled up Pack River to transport the dead men’s bodies back to Sandpoint. Overwhelmed by the desolation, he said, “It was an awesome sight, like lava hot springs. Everything was denuded. Pack River Bridge was just a mass of twisted steel. The heat must’ve been tremendous.”

In the end, the Sundance Fire consumed 55,910 acres. “It was a lost summer,” sighed Eskridge, “when it seemed like the world was on fire.”

For several years after 1967, the area produced millions of mushrooms, particularly morels, which typically follow the path of wildfire. Bumper crops of huckleberries are still harvested there today. The vast landscape in the high country of the Selkirks made naked by the flames has also become a premier destination for backcountry snowmobilers and skiers.

The effects of the Sundance Fire were tragic and the memories vivid. Among those who remember, the hope remains that a fair wind will blow and the thunder will be silent.

Dennis Nicholls was an 11-year-old kid in his native Virginia when Sundance raged in Idaho.

|