Sculpture is about form, whether built up layer by layer, carved away to remove material that surrounds the shape, or assembled piece by piece from selected elements. Among the many artists who call Sandpoint and its environs home are three sculptors who work in different media and styles that illustrate these categories.

David Kraisler’s large wood sculpture “Tolerance” was under construction in September for outdoor installation in the fall near the Bonner County Courthouse. Dan Shook’s tabletop clay piece “Taking Five” was created as the artwork for the 2001 Festival at Sandpoint poster. Chris Bier showed his recycled-copper wall hangings in Artwalk I during the early summer.

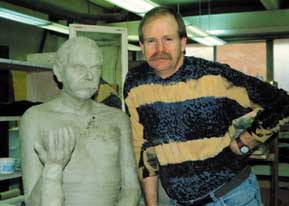

Kraisler, the newest to Sandpoint, has worked as a full-time artist for 30 years as a painter and in diverse sculptural media – cast bronze, steel, ferro-cement, fiberglass, urethane and carved wood. His current pieces are grand-scale constructions of timber and metal. “Tolerance,” for example, is 10 feet tall, and his next piece, designed for the Train and Timber interpretive center in Kootenai, will be 20 feet tall and made of 30-inch-diameter Douglas fir logs. bronze, steel, ferro-cement, fiberglass, urethane and carved wood. His current pieces are grand-scale constructions of timber and metal. “Tolerance,” for example, is 10 feet tall, and his next piece, designed for the Train and Timber interpretive center in Kootenai, will be 20 feet tall and made of 30-inch-diameter Douglas fir logs.

Originally from New York, Kraisler studied architecture at the University of Oklahoma. He worked as an architect in Phoenix and in Los Angeles, where he studied sculpture at the Otis Art Institute. Soon after, he returned to Arizona and made the shift to a full-time art career, and says, “I haven’t worked for anybody since 1972.” He was a partner in a bronze foundry for a time, but says he “has been lucky to be able to do it without having another kind of job.”

In these works, he says, the sculptor’s role is more that of a designer. He designed “Tolerance” with all its steel connections and “strange angles and complex curves,” but the actual construction and metal fabrication are being done by local people.

He says he’s also “learning a lot about logs.” Because of the way the bark is being removed, the timbers in this piece will have a dimpled texture. And the steel connections, he says, “will give the piece a certain contemporary aesthetic. A different bark-removal technique will give the timbers in another piece a smooth texture.

Environ-mental pieces are much more exciting,” he says, than those that stand apart. “They incorporate various ways of viewing them. Large pieces are part of an architectonic space.” And, he says, a large public sculpture must also be created on a scale that harmonizes with the way human beings perceive and interact with sculpture.

Moving up to a grand scale indeed, Kraisler has started models for “cathedral effect” pieces in timber that will stand 50 feet tall. Other pieces currently taking shape in Kraisler’s studio take the construction aspect of sculpture even more literally. He is using steel reinforcing bars – rebar – to create a series of “drawings in space.”

David Kraisler has work in public, private and museum collections across the country. He recently donated a piece to Boise State University. Another is in the Runnymeade Sculpture Farm south of San Francisco. And he has outdoor, public sculptures in Des Moines, Iowa; San Diego, Calif.; Vail, Colo.; and at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in Washington, D.C. His work can be seen in Sandpoint at the Chris Kraisler Gallery, 517 N. Fourth.

Dan Shook has been teaching art in north Idaho since 1978, starting at Stidwell Junior High, moving to Bonners Ferry High School for a few years and then transitioning to Sandpoint High School. Although he paints and works in other media, he started shaping clay some 14 years ago. He “got into clay along with the students (at Bonners Ferry),” he says. He had taken a sculpting class while studying painting in college and later “laid off of it,” but this time the medium held his attention. Dan Shook has been teaching art in north Idaho since 1978, starting at Stidwell Junior High, moving to Bonners Ferry High School for a few years and then transitioning to Sandpoint High School. Although he paints and works in other media, he started shaping clay some 14 years ago. He “got into clay along with the students (at Bonners Ferry),” he says. He had taken a sculpting class while studying painting in college and later “laid off of it,” but this time the medium held his attention.

Shook’s clay and ceramic exploration lately is in working with paper clay – clay with 20 percent to 30 percent paper pulp added. Adding any kind of cellulose such as paper, cotton or straw to clay produces a stronger greenware, he says, so the artist can add figurative elements to the work before firing it. The technique is ancient: It was used in China to make the famous, life-size terra cotta soldiers discovered buried in an ancient tomb.

Shook made some life-size figures of his own while working toward his Master of Art in Teaching degree. One piece, “Four Fathers,” depicts his own father at four different stages of life.

The themes of his art tend toward spiritual subjects. “I’m intrigued by the interest that human beings have toward spirituality,” Shook says, “and why people believe in things.” In exploring these themes, he has created a number of mythological figures, pursuing what he calls “the search for non-belief.”

Although Shook has worked in a variety of sculptural media, and he likes both wood and stone, he chooses to stay with clay because it’s “easier to get ideas out without the frustration” that comes with slow and careful work in stone. He quotes Picasso to describe clay work as “sculpture without the tears.”

The start of the school years is, of course, an intense time for a teacher. As the year goes on and students settle down to their own projects, Shook works on his own art more – where students can watch his progress. “I think it’s good for them to see the teacher working on a piece,” he says.

Eventually, Shook says, he wants to build a studio on property located on Boyer Slough near Kootenai and teach adult classes. Until then, he’ll continue to inspire high-school students on making art of all kinds and to teach them about art theory and history.

Dan Shook currently has some pieces on view at Panhandle Art Glass, 514 Pine Street, and at Eklektos, 502 Church.

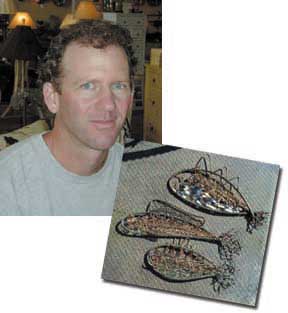

Chris Bier’s constructions are fashioned from recycled copper – “everything from battery cables to old telephone wire,” he says. Most of them are designed as wall hangings. Bier searches the collection bins at salvage yards for interesting materials and buys his reusable copper by the pound. Chris Bier’s constructions are fashioned from recycled copper – “everything from battery cables to old telephone wire,” he says. Most of them are designed as wall hangings. Bier searches the collection bins at salvage yards for interesting materials and buys his reusable copper by the pound.

His “real jobs” in carpentry, forestry projects and landscaping assist him in the quest, because the job sites are also promising as sources for bits of scrap. Friends even save copper for him.

Bier has been in the Sandpoint area for about 12 years and working in copper for about 10. Just before moving to Sandpoint from California, he spent four months on the road. While visiting friends in Vermont, he enrolled in a month-long workshop at the Vermont Marble Company and learned the fundamentals of carving marble.

He arrived in Sandpoint with a carful of marble and now has “about five tons.” Bier’s carvings are primarily stylized animal figures such as a bear “with no eyes or fangs, but it’s definitely a bear.” The work requires starting with big hammers, moving step by step through smaller and smaller hammers as the patterns, forms and occasional fossils in the marble are revealed. In the final stages, finishing with sandpaper, the artist must handle the work with great care to prevent scratching.

Working with copper, then, is far less delicate in terms of handling the sculpture and its elements. If Bier wants to incorporate a bit of tubing into a sculpture, he can flatten it, bend it – by hand, not with tools – and place it. He has also made figure-eight rain chains to go on downspouts. The copper works up quickly, too, he points out, enabling him to make a number of pieces in much less time.

“There are so many people in Sandpoint who have a ‘real job’ and are creating phenomenal artwork on the side,” Bier says.

Chris Bier’s work can be seen at Eklektos Gallery.

These three sculptors are a few of the artists in our neighborhood – drawing in space, forming clay into figures, weaving together metal and polishing stone.

|