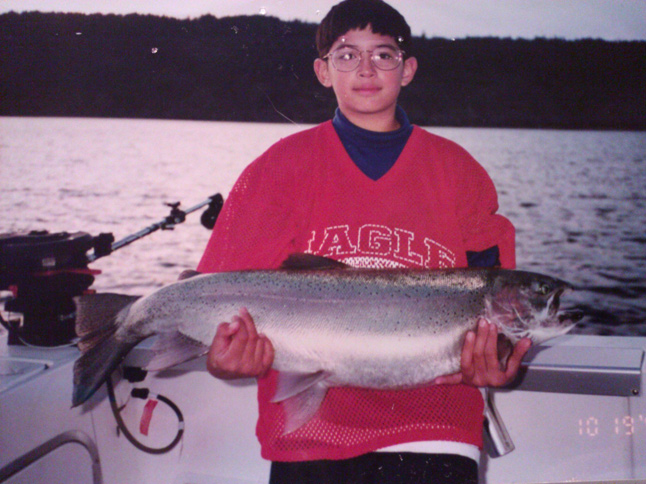

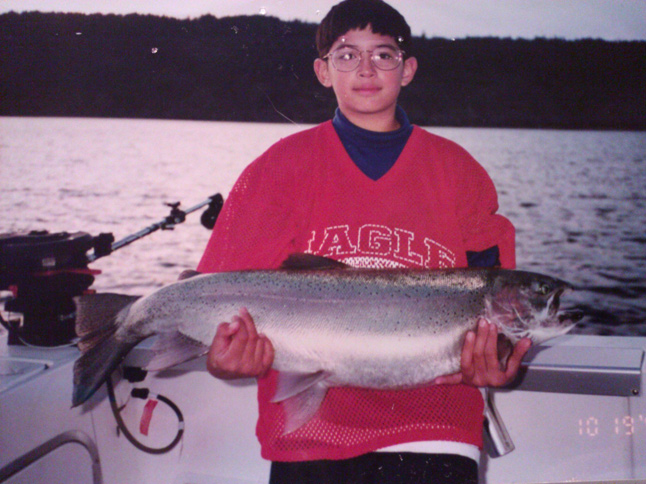

Josh Stokes, at age 10, caught and released this 36-inch rainbow trout Oct. 19, 1997

A storied fishery

Recovery efforts putting the K&K back into Lake Pend Oreille

By Ralph Bartholdt

When Josh Stokes was a boy he stood in the back of his father's boat in his pajamas hoisting a fishing pole.

His dad, Roy Stokes, 56, often carried him from his bed to the pickup, then to the boat in early daylight that waxed over Lake Pend Oreille like a brush stroke.

When he was old enough to shuck the pajamas, the younger Stokes caught his first Kamloops rainbow on the lake, and like the fish, the experience hooked the boy.

"There's nothing like standing on the back of the boat with a 20-pound trout peeling 1,000 feet of line off your reel three times," Josh Stokes, now 23, says. "It's out there 500 feet and still jumping."

As long as anyone can remember, Kamloops has been king fish on northern Idaho's big lake, with fishing derbies that used to pay out $1,000 in the youth division, a prize Josh Stokes pocketed more than once.

During bygone derby days, the roads leading to the lake's boat launches and the resorts that sponsored the derbies were bumper-to-bumper with cars, pickups and boat trailers whose owners and crew were out to land the biggest Kamloops rainbow to win the prize and prestige it brought.

"The grand prize in the spring derby used to be over $20,000," Roy Stokes said. "Now it's $800."

Sportsmen and women would come from across the continent to hook gymnastic Kamloops – also called Gerrard rainbows – in Lake Pend Oreille, watch them catapult into the air, wrap fishing line around outboards and generally give an angler a good show.

Of all the rainbows Roy Stokes caught in 20 years of fishing Idaho's biggest lake, he kept only three, including a mounted 25-pound, 12-ounce rainbow that hangs in his Post Falls living room.

"We almost always let them go," he says. "They were like our pets."

In the historic days of the lake's super rainbow fishery, the lake's kokanee population – the major food source for big rainbows – was at its prime, too, so sport fishermen and meat anglers who caught their limit of the small, silver, landlocked kokanee salmon for the smoker, co-existed happily on northern Idaho's big trout pond.

Those were the good times.

Like many good times, however, shadows loomed and grew, not on the horizon this time, but under the lake's Aqua Velva blue surface.

These shadows were fish too, namely lake trout, a species that was introduced in 1925 by the federal government as a food and possible income source for area residents.

The idea was to provide a commercial fishery for anglers, but the lake trout, transported from the Great Lakes, didn't respond well to their new environment.

The fishery didn't flourish and Pend Oreille's lake trout were destined to sulk around the deep, cold contours of the lake while sport anglers chased the glitzy Kamloops and meat fishers filled buckets with kokanee.

For more than 50 years, Pend Oreille's lake trout – also called mackinaw – were not bothering anyone, says Mike Hansen, a fishery biologist and consultant to Idaho Fish and Game (IF&G) and the Lake Pend Oreille Fishery Recovery Task Force, which have wrestled with the lake's fishery issues for several years.

"The lake trout juveniles didn't have a good food supply," said Hansen, who is a lake trout expert and professor of fisheries at the University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point. Therefore, the macks didn't thrive.

Some time in the late 1960s, Ward Tollbom remembers attending a meeting of sportsmen at Sandpoint Community Hall. An avid fisher of kokanee and lifelong Sandpoint resident, Tollbom and a packed house of anglers, all spurred by the notion of bigger, fatter kokanee in Pend Oreille, demanded IF&G supply a food source for their kokanee.

From left: James Mullen with a 24-pound rainbow. Boots Reynolds shows off 23 lake trout reeled in with Ward Tollbom in three and a half hours June 24, 2008. Dave Ivy caught this sizable lake trout under a bounty program aimed at the unwanted predator

In British Columbia, from where kokanee hail, the trout could weigh a hefty 3 to 5 pounds, while Pend Oreille's kokanee were measured in inches – somewhere around 10 inches was the average.

The only difference was their food source. In British Columbia's Kootenay Lake, kokanee fed on a little freshwater shrimp called mysis.

The anglers at the meeting wanted mysis in Pend Oreille to bolster their kokanee, Tollbom recalls.

"People had visions of tying up to the Long Bridge in the morning and catching 2-pound kokanee," Tollbom said. "We all saw the mysis as the vehicle to do that."

The state fisheries department conceded, and mysis shrimp were introduced. The effect was sweeping and almost caused the demise of the little silvery salmon.

"After the introduction of mysis, lake trout started increasing in abundance," Hansen said.

The S-curved shadows under the lake's surface began to swell.

Unlike both kokanee, which have a four-year life cycle, and rainbows, which grow big and fast with the right food source and usually die before their ninth birthday, lake trout can live to be 65, all the while growing and devouring kokanee, rainbows and their own species.

In other lakes where they were introduced, such as nearby Priest Lake and Montana's Flathead Lake, macks, driven by voracious appetites and the right conditions, have depleted all neighboring fish species on their way to becoming the sole proprietors of their ponds.

This phenomenon became apparent in Pend Oreille in the last couple decades until it reached a climax in 2000.

Bolstered by the introduced mysis shrimp as a food source for juvenile mackinaw, and plenty of kokanee for adults to eat, lake trout populations had picked up speed. At the same time, populations of kokanee, the backbone of the lake's world-class rainbow fishery, slumped.

Because of drastically depleted numbers, IF&G in 2000 closed the season on Pend Oreille kokanee, the landlocked salmon that formed the basis of the lake's multimillion dollar fishery.

Mackinaw, which eat about 10 pounds of smaller fish to gain a single pound of their own, had outgrown their welcome.

"They are bad neighbors," Roy says.

Introducing mysis shrimp to the ecosystem not only helped fatten juvenile mackinaw, but the shrimp also competed with kokanee fry for zooplankton, the fry's main food.

The shrimp were not the only enemy of Pend Oreille's kokanee. A dam completed on the Pend Oreille River in 1955 as a means to churn electricity for the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) had its impact as well.

Built and managed by the Army Corps of Engineers for BPA, Albeni Falls Dam was a feat of modern engineering that supplied needed power for a burgeoning region. By the mid-1960s, seasonal dam operations routinely fluctuated the level of the big lake. Winter drawdowns, it was later learned, uncovered the beds of late-spawning kokanee that rely on shoreline gravel to lay eggs. Early-spawning kokanee migrate to streams in the fall to spawn, but the bulk of the lake's kokanee use shoreline beds to spawn in November and December. The winter drawdown of the lake exposed and killed fertile eggs of winter-spawning fish. Early spawners are also vulnerable to weather, when rain-on-snow events wash them out.

In recent years, the Corps and BPA have worked closely with state fishery biologists to make sure the beds are adequately flooded in winter to assure kokanee survival.

"Lake levels are set going into the winter, based on what biologists believe the kokanee spawn is going to be," said Mike Milstein, of BPA's public relations. "Based on that number, we know we need so much spawning area, so the lake needs to be at a certain level to provide the spawning area the fish need."

The Corps draws down the lake to a level spawning kokanee require.

"We don't want to leave eggs exposed," Milstein said.

Noxious weeds, pollutant-laced runoff and lake drawdowns impact the fishery, but predation of kokanee – the lake's backbone species – is recognized as the biggest factor to the small, blue-backed salmon's survival.

"Ecologically, it's called a predator pit," said Hansen, "when there is too few prey for the predators."

Offsetting the "predator pit" was IF&G's main concern when it started a program more than five years ago to eliminate kokanee's main predators. It includes a $15 bounty on lake trout and Pend Oreille's prestigious rainbow trout.

The bounty, or angler incentive program, combined with commercial fishing of lake trout using gill nets and fish traps in mackinaw spawning areas, were launched when biologists were aghast to learn that after years of battling for survival, Pend Oreille's declining kokanee population was on the brink of total collapse.

"If someone had told me that we could get the kokanee population back in a few years, I would have said they were crazy," Idaho Fish and Game Commissioner Tony McDermott of Sagle said.

McDermott had watched the kokanee's decline for decades and wasn't surprised when it bottomed out.

He and department officials worked with sporting, recreation and environmental groups to form the Lake Pend Oreille Fishery Recovery Task Force that works in concert with state-funded kokanee recovery efforts on Pend Oreille.

The work has paid off.

Hatchery crews collected more than 10 million kokanee eggs and handled about 100,000 late-season, spawning hatchery fish in the 2010-11 spawning season. The egg take ensures an abundant class of kokanee fry will be introduced into the lake this year.

"We've seen major gains in the number of hatchery fish returning in the last two years," Andy Dux, IF&G fishery biologist, said. "In the two years prior to that, we had less than a million eggs each year."

In addition, more shoreline spawners have been recorded.

"Historically they comprise the majority of Lake Pend Oreille's kokanee," Dux said. "They are our ticket to recovery."

Combined with commercial harvesting of lake trout, and a bounty paid to anglers, more than 115,000 kokanee-devouring mackinaw have been removed from the lake since 2006.

For anglers who were getting used to lake trout as a game fish that fetched $15 per head, macks have become harder to find. The ones anglers hook are smaller than the fat, split-tailed fish they caught in the past.

"Fishing is getting tougher," Dux said. "Folks are turning in smaller lake trout. Big ones are harder to come by."

Despite the successes of the lake trout netting and angler incentive programs, he said IF&G will not slacken its grip on getting rid of the lake's macks in its efforts to reach a goal of once again having a kokanee fishery in which anglers harvest 300,000 of the silvery salmon annually.

"The big picture outlook is to continue an aggressive approach to reducing predators," he said.

Since 2006, the angler incentive program has also resulted in the demise of 32,954 rainbows.

Roy Stokes, the man who killed only three rainbows in the 20 years he pursued them for sport is part of the effort.

"I've killed thousands," he said. "Last year I killed 600."

The experience has left him a little sideways.

"It changed me," he said. "We used to turn every fish loose. Now we have to kill them and cut their heads off. It's an emotional, hard thing to do."

For Roy, a member of the task force, and his fellow rainbow trout anglers, there is a silver lining.

As lake trout numbers fall off, and kokanee numbers bounce back, the size and population of rainbows is also ticking upward.

"We saw more rainbows over 15 pounds last year than we have in quite a number of years," Dux said. "It's been quite some time since we've seen as many big rainbows."

The driving force behind the bigger rainbows is the increased number of the smaller kokanee, their food source.

"Really what's driving it is we have seen more kokanee," Dux said.

That means more rainbows are getting fatter as their food source returns, and competition with lake trout, the target of gill netters, eases.

Despite a Lake Pend Oreille kokanee fishery that seems to be rebounding, nobody is standing around waiting for a high five.

"A lot of folks are excited that we're seeing an increase in kokanee and a decrease in lake trout, and more big rainbows than we have seen in years," Dux said. "But we're cautioning them that we have a long way to go to get to our recovery goals. Kokanee populations are still at risk."

Roy Stokes agrees.

"There's no way we're out of the woods," he said.

Sure, he wants to reach the day when he can once again catch and release trophy rainbows, but he is realistic.

"We're not there," he said. "Whatever it takes to get there needs to be done."

Even if it means killing the fish he loves.

From lake level management, to the introduction of mysis and management of the big lake's fish, many of which were also introduced into Lake Pend Oreille, the task of volunteers and IF&G to restore a once-renowned fishery has been a balancing act.

"It's a big lake," Dux said. "It's a complicated lake. We've got a lot of work going on to understand what's going on. It's a complicated story."

But, it's one worth telling.

SIDEBAR

Record-setting waters

Lake Pend Oreille's lunkers for the record books

That Lake Pend Oreille is the state's biggest and deepest body of water is a distinction not lost on sport anglers around the globe.

And like unusually eclectic cuisine, it is served with its own dose of anticipation.

From north to south, the lake stretches 43 miles, covering a surface of more than 150 square miles and plummeting to depths of more than 1,000 feet – making Pend Oreille the fifth-deepest lake in the nation.

Such a trench must hold a variety of fish. Many sport fishers will attest to it. For some, though, the days of testament, or oral observation are left to words printed in Idaho Fish and Game ledgers.

|

Wes Hamlet caught this world-record rainbow trout, a

37-pounder, in 1947 |

Wes Hamlet is a name that has stuck in the record books for more than a half century. In 1947, he hoisted a world-record 37-pound Kamloops rainbow trout out of the lake's cerulean waters. Some say it's still the world-record fish because two subsequent world-record rainbow caught in 2007 and 2009 in Saskatchewan, Canada, are "genetic cheats," genetically modified hatchery fish called triploids – not wild, spawning trout. The International Game Fish Association, however, does not recognize the distinction.

A couple years after Hamlet's famous catch, in 1949, a man named Nelson Higgins caught what remains as the world-record bull trout in Pend Oreille. The fish weighed 32 pounds.

Pend Oreille's waters churned for a while as the lake's reputation as a world-class fishery blossomed. Stories of big Lake Pend Oreille trout circulated and sportsmen anxiously waited for the next record-book trout to be pulled from the lake. Expectations culminated in 1991 with a 24-pound cutthroat/rainbow trout hybrid, called a cutbow, caught by Irwin Donart. The record has stood for 30 years.

In 1995, Jim Eversole caught the largest game fish ever taken from Lake Pend Oreille, a 43-pound, 6-ounce mackinaw, also known as the lake trout.

The lake is little known for its whitefish fishery although it holds in abundance two species of the tender-fleshed fish. The mountain whitefish, a native, is the smaller of the lake's two varieties and found in depths of less than 50 feet.

Introduced into the lake in 1898 from the Great Lakes, the bigger lake whitefish are found at depths between 80 to 200 feet.

The state record lake whitefish weighed 6 pounds, 8 ounces and was caught in Pend Oreille last year by Dale Hofmann.

– Ralph Bartholdt

|