|

'A place to build a House on'

David Thompson, Kullyspel House

and the Indian Meadows tribal encampment on Lake Pend Oreille

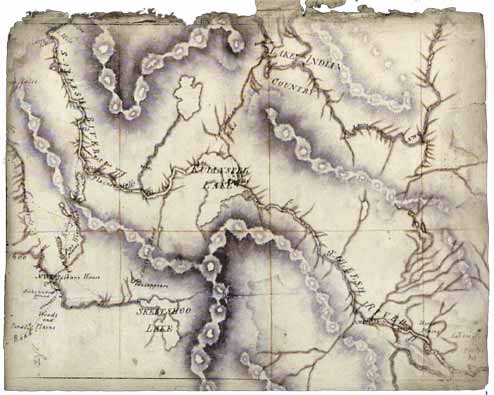

"Map of North America from 84º West," David Thompson's 1820 map prospectus, shows Lake Pend Oreille, center, as Kullyspel Lake. (Public Record Office, Kew, England) |

By Jack Nisbet

In the fall of 1809, North West Company fur agent and surveyor David Thompson established a trading post on the Hope Peninsula, marking the first documented business operation between tribes and traders in what is now the state of Idaho. This year, the Thompson Bicentennial is commemorated in Bonner County, recognizing his arrival at Lake Pend Oreille 200 years ago.

David Thompson was an English-born fur agent, surveyor and cartographer who worked across the breadth of the North American continent between 1784 and 1846. Over the course of his long career, he left behind more than 100 densely written field and survey journals, watercolors of Western mountains, extensive letters concerning his duties with the International Boundary Survey in all five of the Great Lakes, and an unpublished autobiography full of wide-ranging adventures and good humor.

He also drew numerous exquisitely rendered maps, including five large visions of the continent that stretch from Hudson Bay and Lake Superior west to the Pacific. As scholars bring these documents to light – a newly annotated three-volume edition of Thompson's autobiography and letters will appear this fall – the man and his work are becoming much better known in both Canada and the United States.

Some of David Thompson's most interesting and significant exploits occurred during the five years he spent in what fur companies called the Columbia District, between 1807 and 1812. As an employee of the North West Company, he was charged with establishing a viable circle of trade along the middle and upper Columbia River and its major eastern tributaries; in order to accomplish this, he and his crew had to make first contact and create working relationships with a number of Plateau culture tribes. As the fur traders made their way through the territory we now call southeastern British Columbia, western Montana, eastern Washington and the Idaho Panhandle, the trails and waterways they traveled all seemed to converge at Lake Pend Oreille.

Coming in on the lake

Thompson waited a long time to get to the lake. He probably first heard about the promising beaver lands west of the Rocky Mountains in 1787 when, as a boy of 17, he wintered with a small group of traders in a Pikani Blackfeet encampment near modern Calgary, Alberta. Kootenai people who occupied the upper reaches of the Columbia and Kootenai drainages made regular buffalo hunts on the prairies at that time, often joined by Salish-speaking kinsmen that included Flathead (Bitterroot Salish), Kalispel, Spokane, Coeur d'Alene and other Plateau tribes. The Blackfeet smoked, gambled, raided horses and sometimes fought with these visiting hunters, creating a wealth of stories that stretched back and forth over the Continental Divide.

In the fall of 1800, David Thompson learned more about our region when he spoke with Blackfeet leaders about extending his company's trade across the mountains. The elders complained that such a move would only serve to arm the "Flat Heads," a traditional Blackfeet rival, and further warned the trader to beware of Flathead ambushes in the foothills.

Salish vocabulary written by Thompson

|

That same fall, a band of Kootenais crossed the Rockies with pelts to trade. After bartering with them at the North West Company's Rocky Mountain House post on the Saskatchewan River, Thompson dispatched two of his French-Canadian voyageurs back with the Kootenais to scout the Columbia drainage for future business prospects. According to tribal oral histories, these two voyageurs traveled extensively through the region, and may well have spent time around Lake Pend Oreille.

It was the spring of 1807 before Thompson himself pushed across the divide with a crew to establish his Kootanae House post at the source lakes of the Columbia River. He brought over 19 people in all, including his half-Cree wife Charlotte Small and their three young children. Although Charlotte did not accompany Thompson on his further explorations of the Columbia District, other voyageur families did come along, and men such as Joseph Beaulieu, Michel Boulard and Augustine Boisverd ended up marrying Kootenai and Salish women and settling down in the region.

Thompson never worked alone, and he always sent men ahead to establish contact with new tribes he wanted to meet. The mixed-blood free hunter and scout Jaco Finlay, who worked with Thompson intermittently for years, provided invaluable assistance in such relationships.

As soon as Thompson established his first post near the town of Invermere, British Columbia, he began sending gifts of tobacco south to the Flathead and related tribes, calling on them to bring their furs in to trade. When some men and women of a Lower Kootenai band who had a village near modern Bonners Ferry came to visit in mid-September, Thompson noted that "these People hunt on the Lands adjoining the Ear Pendant Indians." He never explained the derivation of the term Ear Pendant, but French was the everyday language he used with his voyageurs, and it no doubt represented his own translation of their term Pend d'Oreille. In his later journals Thompson would variously refer to these people as Ear Pendants, Ear Bobs, Pend Oreilles, Kullyspel and Saleesh. Today they are divided between the Kalispel Reservation in eastern Washington and the Flathead Reservation of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in western Montana – home to three tribes, the Bitterroot Salish, Upper Pend d'Oreille and the Kootenai.

|

A Brook, which we followed is 15 Yds. wide, deep and easy Current, crossed to a Rill of Water which we followed down & to the Lake ... then met Canoes who embarked about 20 pieces of Lumber and Goods. We held on 4 or 5 Miles & Put up at 2:30 p.m., the wind blowing too hard for the Canoes to hold on. – David Thompson journal, arriving at Lake Pend Oreille, Sept. 8, 1809

James Madison Alden 1860 "Kalispelm Lake." (NATIONAL ARCHIVES)

Masseslow's canoe 1905, Manning Collection, Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture. The canoes that Thompson saw the Kalispel people paddling had a specific sturgeon-nosed design.

|

Thompson never quite straightened out the difference between the interrelated family bands that make up the Bitterroot Salish, Kalispel/Pend d'Oreille and Spokane tribes, but he did recognize that they spoke a common Salish language. He also understood that they formed a powerful political entity in opposition to the Blackfeet, and that the lands they occupied could provide a potentially rich source of beaver pelts. He tried to follow the Kootenai River to meet them in late fall 1807 and again in spring 1808, but was deterred first by the oncoming winter, then by heavy spring runoff. North West Company business kept him bouncing back to the prairies for the following year, but by August 1809 he had laid out a plan that would carry him south from the lower Kootenai through to the "Ear Pendant" world.

Traveling from Rocky Mountain House across the trail now called Howse Pass in early August 1809, Thompson and his men made their way down to the Columbia River near modern Golden, British Columbia. There they quickly pieced together a canoe from birch bark carried across the divide, then paddled upstream on the Columbia and passed Kootanae House without a pause – that post had served its purpose, and now Thompson intended to implement his original plan of locating in the Pend Oreille country.

The fur brigade crossed the Canal Flats portage and put into the Kootenai River on Aug. 20. Nine days later they reached the vicinity of Bonners Ferry, where a trail Thompson called "The Great Road of the Flat Heads," led south. Over a year earlier, Thompson had dispatched a voyageur named Joseph Beaulieu to live with the Lower Kootenais, and now he sent Beaulieu south to find the Flatheads, or Salish peoples. A week later, Beaulieu returned with 16 tribal men and two dozen horses to transport the North West Company goods south.

Thompson's strategy of traveling during the dry days of late summer paid off as his party easily forded brook after brook that "would have been much wider in high water." Although they had to cut small trees from the sides of the trail to make way for the packhorses, Thompson judged it a "good Road." On Sept. 8, they followed the trail down Boyer Slough to the north shore of Lake Pend Oreille, first viewing the lake somewhere near Kootenai Point. Heading east from there, they soon bagged four geese, three ducks and a sandhill crane for dinner.

- Building Kullyspel House

At a point somewhere between the Sunnyside Peninsula and the Pack River Delta, the furmen were met by several canoes, which took on part of the trade goods in order to relieve the horses. The party continued east the next day along the lakeshore to the vicinity east of the modern town of Hope, Idaho, where they encountered an encampment of Flathead, Kalispel/Pend Oreille, Kootenai and Coeur d'Alene families. As with the Pend Oreille, Thompson used his own English translation of the French to call the Coeur d'Alenes "Pointed Hearts." Thompson wrote:

They all smoked ... say 54 Flat Heads, 23 Pointed Hearts & 4 Kootanaes - in all abt 80 men. They then made us a handsome present of dried Salmon & other Fish with Berries & a Chevruil [mule deer].

For census purposes, Thompson usually calculated six or seven family members for each adult male, so this gathering would have numbered around 500 people in all – exactly the sort of large mixed tribal encampment that called for a trade house. Early the next morning, accompanied by two Flathead men, Thompson explored the Hope Peninsula to look for a place to build. From this day on he called both the lake and his new post after the Kullyspel (now Kalispel), presumably because his guides and translators belonged to that tribe.

Word of the fur company's arrival on the lake spread quickly, and the newcomers had barely set up their tents before family bands began arriving with furs to trade. Sixteen canoes of Coeur d'Alenes paddled up to the peninsula and offered to perform a dance. Fifteen "strange Indians from the west," who may have belonged to the San Poil and Okanagan tribes, appeared. Two "Green Wood" (Nez Perce) men brought beaver, muskrat and bear pelts in exchange for manufactured goods. Thompson gave a demonstration of the way that he wanted different types of skins to be prepared, then encouraged the visitors to hunt beaver and bring in their furs to trade "by the time the Snow whitens the Ground."

While Thompson parleyed, his crew began their routine search for birch to make tool handles and pegs, then felled trees for a warehouse, always the first building to go up. The men were experienced in what is known as the "post-on-sill" method of construction, and they had the tools to do the job: large and small axes, two handsaws, a crosscut saw, and a "whip-pit" saw for felling and shaping trees. They also used an adze and a variety of files and knives to shape the timbers, different-sized augers for boring mortise holes, and a hammer for pounding joints together.

|

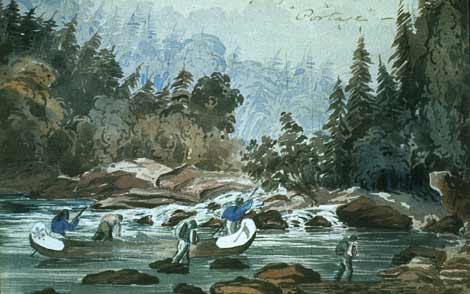

We had no alternative, we carried [the canoe and goods] 2 miles, the 1st mile among broken rocks shivered to sharp, small pieces ... man had two pairs of shoes on his feet, but they were soon cut to pieces. – David Thompson journal, portaging the Kootenai River, May 1808

"Looking for a Portage, McGillivray's River" [Kootenai River]

|

The men sank post holes in the gravelly earth, squared logs for corner and doorframe posts, and whittled "needles" (tenons) to secure these uprights to the horizontal sills. The uprights were grooved to receive members that had been notched and squared to stack up for the walls. The spaces between these "piece on piece" logs was chinked with mud exactly like a rougher, American-style log cabin.

At Kootanae House, the crew had used pine bark for roofing, but since the season was not right for peeling the bark cleanly, here they split out rough planks of cedar instead. Thompson, always picky about small details, groused about the lack of good clay to mix with grass for sealing the cracks between the planks, which would make for a leaky roof. He did allow his clerk Finan McDonald to hang the door. In the months to come, McDonald would take a Kalispel woman he called Peggy as his "country wife" and establish long-term relationships with Kalispel and Flathead families. In time the couple had at least five children, and McDonald played an important role in the Columbia District fur trade until his retirement two decades later.

While the fur traders erected the three buildings that would make up the post, local tribal members provided deer meat, dried fish and many fresh and dried berries to keep them going. People from the encampment also supplied essential goods from local materials that they knew far better than the newcomers. When Thompson decided he needed a dugout canoe for fishing, his voyageurs cut down a large "red fir" but quickly discovered that the wood was too heavy and hard to work. Rather than waste time with that dugout, Thompson instead bartered for one of the Kalispel tribe's light, sturgeon-nosed canoes, sheathed with the bark of a western white pine.

During this period Thompson traded for well over a hundred beaver pelts and gave 15 of them back for a fine horse. He carved out a horse collar and worked on a magazine for the men's powder supply. Thunderstorms raged over the lake as bands of Flathead and Coeur d'Alene people came and went. Jaco Finlay arrived from the Kootenai country with his wife and several children, and Kootenai hunters whom Thompson had known from the source lakes of the Columbia brought in game.

Keen on catching fish to supplement his crew's diet, Thompson carved cedar floats and strung out his fish nets of cotton twine. Over the next several days, he carefully monitored their placement and relative success in an extended fishing experiment. Familiar with the fishing dynamics of prairie lakes in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, Thompson was not pleased with the number of suckers and occasional bull trout that came up in his nets, but like any dedicated fisherman, he never quit trying to catch more.

One of the things he quickly learned was that when it came to repairing his nets, nothing beat twine spun from the Indian hemp plants that grew right in the area. When he hired the wife of one of his Kalispel envoys to provide such twine, she hand-twisted 420 feet in a single afternoon. Thompson, who did not give out compliments easily, pronounced the product "very strong."

-

|

We all arrived at the Saleesh River; here we were met by fifty four Saleesh Indians; Twenty Three Skeetshoo; and four Kootanane Indians, in all eighty men, and their families; they made us an acceptable present of dried Salmon and other Fish, with Berries. – David Thompson, "Travels," iii.215

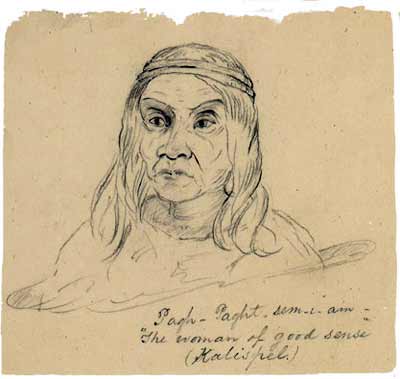

Thompson relied heavily on the plant knowledge and manufacturing skills of tribal women.

(Gustavus Sohon 1853 "Woman of Good Sense, Kalispel"

WASHINGTON STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

Exploring Up and Down the River

By the third week of September in 1809, North West Company voyageurs had moved all their trade goods into the new Kullyspel House warehouse and were starting to construct an upper floor. David Thompson, however, was far from ready to settle in for the fall. Tribal elders had informed him that the Columbia River lay not too far downstream, and he wanted to go "on discovery" before winter arrived – if what he called the "Saleesh River" proved navigable, he might be able to establish a new route across the Rockies that would avoid the troublesome Blackfeet.

Setting his clerk Finan McDonald in charge of the nascent post, the agent engaged a Kalispel teenager to lead him and Joseph Beaulieu downstream. Traveling on horseback, the Kalispel lad followed a trail along the north side of the lake that skirted the wide Pack River delta, then cut across an isthmus (Sunnyside Peninsula) and a sandy point (today's Sandpoint) to the outlet of the Pend Oreille near Dover.

On the second morning, the party continued "on a jog trot all the way" through the glowing fall colors and large, well-spaced coniferous trees. The river was wide and smooth, with plenty of grass along the shore for the horses. By late afternoon they had reached Albeni Falls, where Thompson reconnoitered for a canoe portage and then went fishing in the deep pools below the falls. He caught nothing, but Beaulieu managed to shoot three mergansers for their supper.

At a Kalispel village on the site of modern Cusick, Thompson borrowed another canoe and tested the fast waters of the Pend Oreille River downstream towards Box Canyon. As soon as he confirmed what tribal headmen had already told him – that rapids and waterfalls would prevent the Pend Oreille from forming a viable trade route to the Columbia – he and Beaulieu returned to Kullyspel House. There Thompson was pleased to find that McDonald and his men had completed the warehouse and cut all the timber for a dwelling house. He wrote:

Mr. McDonald had traded abt 2 Packs of good Furrs in my Absence, mostly from the Pointed Hearts (Coeur d'Alenes), of whom there are abt 44 Men, several Women and Children here. They have abt 110 Horses, & have traded 3 of them with us.

The Coeur d'Alenes had been waiting for Thompson's return to "exhibit a Dance," but the weather was cold and blustery, and after two days they decided to decamp.

Thompson spent three more rainy days at the post, resetting some of the fishing nets and helping the men put up the first four layers of hewn logs on the dwelling house. Then, "notwithstanding the very bad weather," he began preparing for another journey – a North West Company brigade was bringing trade goods from eastern Canada, and the time was fast approaching for their projected arrival on the Kootenai River. Taking an opportunity to explore along the way, Thompson and Beaulieu set off eastward on Oct. 11 with a guide and a hunter, along the ancient "Saleesh Road to the Buffalo."

|

The oldest Man according to custom made a Speech & a Present of 2 Cakes of

Root Bread, abt. 12 lbs of Roots & 2 1/2 of dried Salmon, with boiled Beaver Meat.

– David Thompson journal, September 1809

"Indian Fishing Station on the Kalispel Lake and River"

In 1845, a British Army officer painted a watercolor sketch of a Kalispel village near Cusick, Washington, very close to a place where David Thompson met Kalispel people in the fall of 1809. (Henry James Warre 1845)

|

The party traveled up the Saleesh (Clark Fork) River for five days, then embarked on a long counterclockwise loop that cut north across Camas Prairie (toward today's Hot Springs, Montana), up the Little Bitterroot River to a chain of lakes now bearing Thompson's name, and along the Wolf Creek drainage to the lower Fisher River. On Oct. 20, near the junction of the Fisher and the Kootenai, they caught up with the canoe brigade. During the next week, Thompson led the combined party across the Kootenai Falls portage, met horses sent by McDonald at Bonners Ferry, repacked the goods and re-embarked on the Great Road of the Flatheads, which he was now calling the Lake Indian Portage. Despite some nasty weather, the caravan made excellent time on the widened trail and soon completed the surveyor's long circle of reconnaissance. Thompson wrote:

Oct 30. A day of much Snow, but mostly calm & arrived at the House all well, thank Heaven, but much of the Goods very wet, as well as all our own baggage.

Thompson was back at Kullyspel House, but still not settled in. The Indian Meadows encampment was by now completely dispersed, and to follow his trading partners he had to transport his entire operation upstream on the Clark Fork, nearer to Salish, Kalispel and Kootenai wintering grounds. By the end of the first week in November, his voyageurs were banging away on Saleesh House near Thompson Falls, Montana, and Kullyspel House had been relegated to a way station – a warehouse for furs and trade goods along the Great Road to the Buffalo. As far as fur trade journals indicate, the post was never permanently manned by an agent, and after half a dozen years of existence slowly faded back into the woods of the Hope Peninsula.

Found on private property on Hope Peninsula, the currently accepted site of Kullyspel House contains rock piles that are presumably the remains of the building's chimneys. (Photo by Dann Hall)

Jim Parsons Sr. inspects an inscribed tree at the site on Hope Peninsula, circa 1948. It reads "Kullyspell House Duncan McDonald." (Photo by Ross Hall)

Between 1807 and 1812 west of the Continental Divide, David Thompson and his crew of North West Company voyageurs built four substantial trade houses and numerous "hangards," a term Thompson used to refer to temporary rendezvous spots or trade encampments where goods had to be cached. The main posts were Kootanae House near Invermere, British Columbia (established in summer 1807); Kullyspel House near Hope, Idaho (September 1809); Saleesh House near Thompson Falls, Montana (November 1809); and Spokane House near Spokane, Washington (summer 1810).

None of Thompson's establishments lasted for more than a few seasons on their original sites; all except Kullyspel House were eventually moved, rebuilt and expanded. Although a local historian with a shovel established the outline of Kootanae House before World War I, none of the other three sites have ever been systematically explored. In the summer of 2005, a team of Parks Canada archaeologists revisited the Kootanae House location, using both measured trenches and ground-penetration radar to reveal many new aspects of Thompson's two winters at Lake Windermere.

The exact location of any of the other three major posts remains a subject of debate. But while neither Thompson's maps nor his writings contain more than a general area for Kullyspel House, a remarkable visit by a fur trade descendant and a Kalispel tribal man did provide a starting point for any serious search.

As the mixed-blood son of Hudson's Bay Company trader Angus McDonald, Montana resident Duncan McDonald often acted as a bridge between the tribal and white communities during the early years of white settlement in our area. Thus it made sense when the Pend Oreille Pioneer Society, searching for clues about the actual site of the Kullyspel House fur trade post, asked Duncan for help with oral history. Duncan consulted with Alex Kai Too, an aged Kalispel who lived near Arlee, Mont., and was the brother of a former Kalispel chief identified as "Merchelle." McDonald brought Kai Too to the Hope Peninsula in July 1923.

Although Kai Too was blind at the time, he knew the area well. According to a story that appeared in the Sunday Missoulian that September: "Folding his hand like a bear paw, old Alex said: 'Go to Memaloose Island – to a point on mainland – big rock – bear paw – just behind on level ground – you find chimneys.' " McDonald, Sam Owen and other local residents followed the directions, using the island to line up their bearings on the mainland, and found two piles of rocks; "the larger one evidently a double chimney which was constructed of fat stones carried there by no agency other than human hands."

McDonald and Kai Too's visit offers one step toward what could be an illuminating investigation of how the first white visitors interacted with the multitribal encampment at Indian Meadows. Were the rock piles Kai Too pointed at really part of the original Kullyspel House? What was the layout of the buildings? How much business was transacted at the location? Could an American party, as some historians have suggested, have preceded Thompson to the Indian Meadows encampment and built their own hangard?

Local archaeologist Bob Betts points out these questions are a long way from being answered. "There has never been a professional archaeological investigation at the currently accepted location of Kullyspel House site," he said. "At the moment, there is not even a National Register site report on file with the state of Idaho specifically written for Kullyspel House."

Betts' hope is that a growing public awareness of the importance of Thompson's work, combined with the non-intrusive archaeological techniques successfully employed at the Kootanae House site in 2005, might lead to the kind of scientific probe that would not only solve some basic questions about the site, but also expand the story of contact for historians, tribal members and the entire community of Pend Oreille residents.

Betts will be giving a talk on the search for the location of Kullyspel House at the Thompson Symposium on June 25, 2009. See story, page 64.

– Jack Nisbet

|

Remembering Indian Meadows

Coming June 24-27, 2009: Kalispel encampment marks bicentennial

|

Indian Meadows, 1898

We all arrived at the Saleesh River; here we were met by fifty four Saleesh Indians; Twenty Three Skeetshoo; and four Kootanane Indians, in all eighty men, and their families; they made us an acceptable present of dried Salmon and other Fish, with Berries. – David Thompson, Travels," iii.215

|

This June 24-27, Idaho's David Thompson Bicentennial Committee and the Kalispel Tribe will recognize the arrival of David Thompson at Lake Pend Oreille with a variety of events. An all-day teacher's workshop on Thursday at Hope's Litehouse Restaurant features fur trade re-enactors, classroom lesson plans, tribal perspective from Kalispel elder Francis Cullooyah, and an evening canoe paddle for all.

Friday's symposium at the restaurant includes a lesson in celestial navigation with period instruments, as well as presentations that will probe the archaeological search for both the Kullyspel House site and the ancient Salish Road to the Buffalo trail. The symposium concludes with an afternoon panel of distinguished tribal elders discussing the impact of the coming of the fur trade on Salish culture.

After that panel, people who have preregistered will move upstream to the Diamond T Ranch on the Clark Fork River to join Kalispel hosts for a re-creation of the diverse tribal encampment that lured the fur traders to the Salish country in the first place. Look up www.davidthompson200.org or call 263-2344 for more information or to register.

The site of Thompson's Kullyspel House lies just west of the delta where the Clark Fork River spills into Lake Pend Oreille, and there an area of lush meadows had long served as a communal gathering place. Undated bear paw petroglyphs pecked into rock outcrops nearby reach far back into unrecorded history, and after the establishment of Kullyspel House many aspects of the gathering continued on unchanged. Each August, while the area's early white settlers harvested potatoes and hay in the meadows, Salish and Kootenai bands pitched tepees and erected drying racks on their traditional family spots. They played the stick game, raced horses and danced with whomever wanted to join in. Everyone knew the place from present-day Denton Slough east beyond the drift yard at the Clark Fork Delta as Indian Meadows until 1955, when the backup of Albeni Falls Dam drowned the fertile lakeside bottomlands.

Alice Ignace, a Kalispel elder who passed away in 2007, grew up on the Kalispel Reservation near Cusick, Washington, almost 80 miles downstream from Indian Meadows. As a young girl in the 1930s, she traveled with her family by horseback and wagon to camp at the meadows for several weeks in late summer.

"My grandmother, she would sure be happy to get to that place," Ignace said, "because there were always lots of good things out there."

Her father pitched their tepee and set up drying racks with five or six other Kalispel families. They would visit with friends and relatives from the Flathead Reservation, and people from several other tribes would be there, too. While the men went out hunting and fishing, Ignace's grandmother picked berries and dug wapato (arrowhead or duck potato). The berries were dried and then stored in baskets or Mason jars that were wrapped in cloth for the bumpy ride home. Deer meat was sliced and placed on the racks to dry, and the hides were stretched for scraping off the fat. Hundreds of whitefish were split and arranged to dry as well.

"A good hunter always has three racks," Ignace remembered her grandmother saying. "One for meat, one for hides, and one for the fish."

Her grandmother gathered great piles of bulrushes (tules) to sew together into mats, which were used for everything from kneeling pads to place mats to tepee covers. She also cut great numbers of the red stems of Indian hemp. "She would strip all the leaves off each plant, just like that," said Ignace, flinging her hands out like falling leaves. "Then she'd tie them up in a bundle and take them back to Cusick," down the Pend Oreille River.

At home, her grandmother stored the hemp on a rack above the woodstove until it was dry, then soaked the stems and pounded them gently with a stone to remove the pith and separate the fibers. She twisted and braided the hemp into line that was flexible, stout and extremely durable. If her grandmother needed an extra strong cord, she braided a strand of sinew in with the hemp fibers.

"She kept making more and more, winding it all up until she had something that looked like a ball of wool yarn," Ignace said.

The cord was used to attach fish lures, mend nets and sew tules into rain-resistant mats. Sometimes Ignace's grandmother would walk out into the woods to strip long pieces of bark from a cedar tree and then weave it into a basket, tying off the top with Indian hemp.

"It was what she used for anything that needed to be tied," she said. "That hemp was important to have around. And the plants my grandmother liked best grew at Indian Meadows."

– Jack Nisbet

|

-Local man replicates Thompson plank canoe-

Obsessive craftsman ends long-time engineering debate

|

On Gold Mountain lives a man not quite of this century. Not quite a hermit, not quite a mountain man but definitely not embraced by modern society.

Yet this is what made Bill Brusstar, 68, successful in his challenge of recreating and building and finally extinguishing the mystery of explorer David Thompson's cedar-plank canoe.

The 25-foot boat – graceful, light and with the false appearance of simplicity – is a key part of the Thompson exhibit on display this summer at the Bonner County Historical Museum.

Brusstar, with his obsessive personality, couldn't stop with the canoe so he painted a mural of Thompson and a crew member contemplating how to finish the final planks. There's also an oil painting of what the canoe might have looked like as the crew pulled it up the Columbia River toward Kootanae House in the spring of 1811. Then there are the handmade tools, such as the crooked knife and froe, crucial to splitting the cedar planks.

The canoe, which is only partially complete because Thompson's daybooks get scarce on detail, is the only replica in existence of the first cedar-plank boat Thompson made at Boat Encampment, a portage in the Canadian Rocky Mountains where the Columbia River makes a hairpin turn and flows south into the United States.

"I see this as a pretty big deal because Thompson basically developed this new kind of boat," said Ann Ferguson, curator of the Bonner County Historical Museum.

The first canoe leaked fiercely. Thompson kept improving the design and made new plank canoes at each portage, including Saleesh House near Thompson Falls, Mont.

Brusstar used the same materials, cedar and spruce roots, and the same primitive tools – fire, water, an axe and a crooked knife – as Thompson did 200 years ago when he needed a bigger boat to carry more than 2,000 pounds of supplies and furs to his trading posts. To him, the boat was just part of the job.

Bill Brusstar used Thompson's journals to build a cedar plank canoe, now on display at the Bonner County Historical Museum. (PHOTOS BY ANN FERGUSON/BONNER COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

To Brusstar it was a challenge and perhaps a chance to clarify history. Controversy exists among boat builders about how the cedar-plank canoe was engineered, said Jack Nisbet, a Thompson expert and historian.

The biggest question is, Did the thin planks overlap like the European boats often called "clinker built" or were they flush, put edge to edge and sewed together with spruce-root cords?

Brusstar doesn't understand the debate. If you follow Thompson's instructions, it's clear that the planks are flush, he says. This puts the integrity on the cedar planks and less strain on the spruce lashing. Nisbet attributes some confusion to Thompson later using the term "clinker built" to describe his plank canoes.

"There is no guesswork," Brusstar said, somewhat defiantly. "None. David Thompson clearly tells you what to do. And when you do it, you have a boat sitting there. The Thompson historians aren't boat builders."

Brusstar is a boat builder, from a long line of boatwrights going back to the American Revolution. He's also a basket maker, trained by an Alaskan Eskimo. It's this blend of knowledge and his rebellious ingenuity that makes it possible for him to understand Thompson's methodology.

For 15 years, Nisbet encouraged boat experts to replicate the plank canoe – to build it using the journals and resolve the debate about Thompson's canoe that redefined travel on Western rivers. Yet, nobody took on the challenge. Nobody but Brusstar.

"Only an extremely focused person would try to figure out what was going on," said Nisbet, who has no boat building skills. "The journals are so densely detailed."

The other boatwrights Nisbet tried to persuade to build a replica were trained solely in European methods. They never viewed the canoe with a tribal perspective, Nisbet said.

"Being European-trained is a terrible thing when dealing with these wilderness guides," Nisbet said. "They don't do it by the book. They had to figure it out on their own. That's why Brusstar is so perfect."

"I love trying to make something useable and functional out of the woods," said Brusstar, who dug and pulled up miles of root for the project.

Scars in lodgepole pines provided the sap that he boiled over a fire and mixed with lard to seal the seams. After splitting a cedar log into thin boards, Brusstar cured the wood by soaking it and then shaping it over a fire with molds and steam.

"When building a boat you know exactly what is going on," Brusstar said. "The same problems I ran into he ran into. That's why I say it's like channeling the guy. It really opens up a window of history to me."

Brusstar spent years studying about 40 pages of Thompson's journals, full of 200-year-old English, complicated calculations and boat jargon.

These pages provide a recipe for the canoe, which Thompson improvised because birch bark was too thin and inferior west of the Rockies. Cedar was plentiful, causing Thompson to combine his European boat-making skills with his ability to make canoes in the tribal tradition of the Kootenai and Kalispel.

The detailed descriptions stop as Thompson gets near putting the final planks on the bottom of the canoe. Brusstar stopped construction in the same spot.

"The planks start taking on a strange shape," Brusstar said with a heavy sigh. "I have a feeling he was cutting and fitting and doing a lot of shaping to get them to fit. The journal gets sketchy."

Both Ferguson and Nisbet want Brusstar to complete the canoe.

Brusstar is conflicted. He wants an exact reproduction, yet it isn't exact and never will be because the wood and roots are different than in 1811. That's a reality of the changing environment and the impacts of logging and civilization.

"These guys did this all their lives and they knew what they were doing," Brusstar said. "I don't know what I'm doing, but I do have a vague idea."

– Erica F. Curless

|

|