Curt Hecker,

By David Gunter

"I've never worked this hard in my life," Curt Hecker says from a swivel chair at the head of a long wooden table in the third-floor boardroom of the Panhandle State Bank building. And then he smiles.

Hecker, the president and CEO for the bank's parent corporation, Intermountain Community Bancorp (IMCB), comes across as a seasoned competitor itching to stay on the field in the last quarter of a big game. Decades after playing football as an inside linebacker for Boise State University (BSU), he still has the look of someone who could – figuratively or literally – knock you on your butt if you got between him and the goal line.

After earning a degree in business management from BSU and later graduating from the Pacific Coast Bankers' School at the University of Washington, Hecker began his career at West One Bank in 1984 before joining Panhandle State Bank as its president in 1995, a time when its branches were limited to Sandpoint and Bonners Ferry. Publicly traded as IMCB and headquartered in Sandpoint, it now operates a network of 18 community bank branches in Idaho, Washington and Oregon.

The size of the parent company and his seat on the Coldwater Creek board of directors – a post he has held since 1995 – work together to explain some of Hecker's recent hard work, but a bigger part of the story can be attributed to hard times for the economy as a whole.

Although it remains well capitalized when compared with big banks that seem to monopolize the financial news headlines, IMCB also has struggled of late, reporting a net income of $1.2 million for fiscal 2008, compared with the $9.4 million reported in the prior-year period. As if that weren't enough to keep a CEO up at night, Hecker was contacted last fall by the FDIC, which offered up $27 million in so-called TARP funds as part of a U.S. Treasury program to infuse new capital into the banking system.

After weighing the pros and cons of taking the money, he decided that the federal government was handing him the ball – so he took it. While many of his peers were cutting their operations to the bone and moving to the sidelines, Hecker said he saw a chance to score big for the communities he serves. His description was just one more example of the sports metaphors that pepper his speech as he defines his approach to life and business.

"It comes down to an attitude," he says. "To use a football analogy: We're in the game and we've got to play. It takes both offense and defense to win, but in the end, it takes points. The outcome is going to determine whether a play was a good play or not. Operating from a position of absolute strength gives me confidence that I'm prepared and I'm going to win the game."

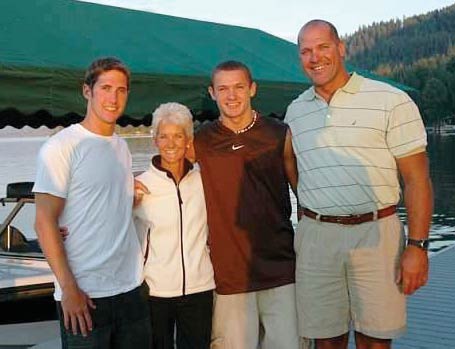

Hecker, 48, lives in a home along the Pend Oreille River with his wife, Barb, and son Cody, a junior at Sandpoint High School. Their oldest son, Chad, is a junior at Hecker's alma mater, BSU.

Spending time with his family – whether on snowy peaks or out on the lake depending on the season – is this executive's highest priority. He regrets that his time with them has been at a premium for the past year, but he seems energized by the chance to act as coach in the midst of the most difficult economic environment of his professional life.

The Hecker family, from left, Chad, Barb, Cody and Curt, spend much of their family time recreating on the lake. The Hecker family, from left, Chad, Barb, Cody and Curt, spend much of their family time recreating on the lake.

|

What do you do to blow off steam?

The thing I do is spend time with the family. That time is really valuable right now. In winter, when I get a chance, it's grab my skis and snowmobile and go up to Roman Nose or Trestle Creek. We take the snowmobiles up, hike the hill and then ski down and spend the day just being out in the snow and sunshine. That's when I really can download. Being on the water is also huge for us, whether it's fishing or waterskiing, wakeboarding or just going for a cruise on the lake. It's a family event where we can be alone together and it's a big stress reliever.

Does your family still start the day by going out on the lake?

Yep. We get a good seven or eight months' worth of waterskiing in every year. It's a 4:30 wake-up call and by 5:30 we're starting to make the first passes. We usually spend an hour and a half out there while the sun's coming up and the fog is lifting off of the lake. It's a very enjoyable thing to do before you have to start thinking about work for the day.

What, if anything, did you learn from playing football that's coming in handy in this business environment?

A lot of success in my life has come as a result of competitive sports. What I learned is hard work and being able to persevere under adverse situations. You can draw a lot of analogies from sports life to academic life to business life where you face things that are hard to overcome. And there's stress and fear within all of them. How to control yourself and control your thoughts is something that I learned very early on. Fear is a good motivator and it's not necessarily all negative. The stress, when it's under control, is something I find is healthy. It's something I learned in college football.

That's a good bridge to the recent financial news. How much psychology do you think is behind the current economic malaise and how much of it is based on reality?

A large amount of it is based on fear. There are two factors, and I'd weigh them about the same. First, the public's confidence in the financial system is a major concern that we have to overcome. That exists because there were fundamental decisions that were made that caused that distrust. Without recognizing what the problems are and putting things into place to correct them, we can't deal with that confidence. The problems we've had are common sense-oriented. As individuals and as a country, we lost our common sense. If we're going to point a finger or look for someone to blame, we have to point the finger at ourselves, because we're all part of this. In banking, virtually all of us can sit back and say that we saw people – we might have even participated in helping people – get into loans that they just couldn't afford. It just didn't make good common sense. As a country, as a globe, as a community, it went on for years and we were all thinking that the bubble would never get too big and that the economy would never burst. But it did.

With all the bad news surrounding the big banks and the bailouts needed to prop them up, could we be entering a new era where people rediscover the value of small, community banks?

(Photo by Patrick Orton) (Photo by Patrick Orton)

|

I think we're seeing that right now. There are roughly 8,000 banks in the United States and, of those, 19 of them control two-thirds of the total domestic deposit base. So that leaves community banks with the other third. For the most part, those community banks are healthy. They're not the ones who started this mess, but they're certainly getting rained on by the issues that the larger banks have had and will continue to have going forward. In my world – the world of community banks – things are pretty simple. It's still about relationships. We take customers' deposits and we loan it back to small business customers, or loans for a house or a car. That really doesn't change for us. What will change, for the big banks, is that their mass-transaction products won't exist anymore. Community banks will continue to benefit from that as market share moves away from the larger institutions to a more localized scenario.

When you learned that IMCB was eligible for $27 million in federal funds, what mental gymnastics did you go through as CEO while deciding whether to accept it or not?

Between Christmas and New Year's was a real soul-searching time for me, to determine whether we take the money and what is the right thing to do if we do take it. A lot of things were going through my mind as a result of what had happened to the economy, but what was important was preparing for the future and a lot of uncertainty. My first thought was, Do we hold our cards and just sit back and let things happen? That would have meant playing an ultra-conservative role by laying off a significant number of employees and preparing to deleverage the company. Many bankers have done that. While we were and are well-capitalized, what it came down to for me was that, if I took these dollars, I needed to defend and protect the bank with them. But I also needed to play offense. It all comes down to leadership. I think the future of banking is wonderful, but if we're scared of it, we're going to miss opportunities. I guess I'm still young enough at this point and competitive enough that we can play. Not without risks, but we do need to play. ... We knew we wanted to take this thing forward and continue to invest in the community. That's where the "Powered by Community" concept came from.

That's meant to be a local stimulus plan, right? How does it work?

Right now, loan demand is down and we need to get it back up in a prudent way. Powered by Community is designed to put in an organizational structure to work with community leaders, groups, nonprofits and whatever economic stimulus is going to be coming down so that we are prepared to get dollars and find ways to make loans in our community. The idea is to work with the communities we serve to design the products and services they need with them so that we can get those dollars out. The other phase of this is a commitment to take on 100 new projects and challenge other banks and their people to take part. There are thousands of projects out there that need to be done. It's not a product, it's a process. I envision this going on for many years as we work through the economic issues.

If you could write how this chapter of your life comes out, what would you like to be saying about how you handled this challenge?

I'd like to be able to say that I learned a ton from the experience and that I learned to control fear by going through the process. I also want to be able to say that I learned, once again, about the need for perseverance. Back in 2005, we all said, "The sky's not going to fall – buy, buy, buy," and we lost respect for how materialistic we had become. And how greedy. More than anything, I'd like to look back and say that we learned a wonderful lesson and brought back traditional values. I'd like to say that we found the answer to the question of how our kids and grandkids were going to be able to have the same kind of quality of life that we had. We're living through an important part of history. I want to say that we learned to deal with what we had to deal with. I would never want to go through it again, but I'm damned glad I did, because it made me a better man.

|